At a certain point during our weekly worship gathering, I get to stand up and lead our church in a modified version of the prayers of the people. We always begin this movement of worship with silence and then confession. The silence lasts somewhere around fifteen seconds, although I always shoot for thirty. As little and insignificant as that may seem, it's intentional; and because it's a part of the liturgy of worship it's deep with meaning.

Chapter three of Dennis Okholm's book, Monk Habits for Everyday People, is called "Learning to Listen." (Read my first post here.)

Silence is not just about not talking. In fact, Benedict never urged for total silence. The restraint of speech was a matter of hospitality. Because they all lived together in a monastic community, silence was encouraged over an excessive amount of talking. Thus, one should speak only when words were necessary. Of course, this begs the question as to how one knows when words are and are not necessary. This is partly why this community practiced intentional times of silence. If you never stop talking then you are not able to know when is the right time to be silent. By practicing silence we learn when to speak and when not to speak. Of course, when they spoke intentionally it was in the form prayer, specifically reading the Psalms. This says a lot about how we learn to speak as Christians. When you begin to follow Jesus, you are just not able to speak maturely about Him. You have to learn how to speak and the Psalms, for example, can train us in this. Consider that Paul spent fourteen years after his conversion learning before he spoke in any sort of public and authoritative way. This should make us pause.

Okholm quotes Michael Casey on this, a point speaks to North American cultures situation of just utter noise. "Talk restricts our capactiy to listen, it banishes mindfulness and opens the door to distraction and escapism. Talking too much often convinces us of the correctness of our own conclusions and leads some into thinking they are wise. IT can be a subtle exercise in arrogance and superiority. Often patters of dependence, manipulation, and dominance are established and maintained by the medium of speech."

In case you're ever wondering, this is why we take time to be silent in worship. Too much is riding on the church's capacity to know when to speak and when to be silent, as well as how to speak and how to be silent.

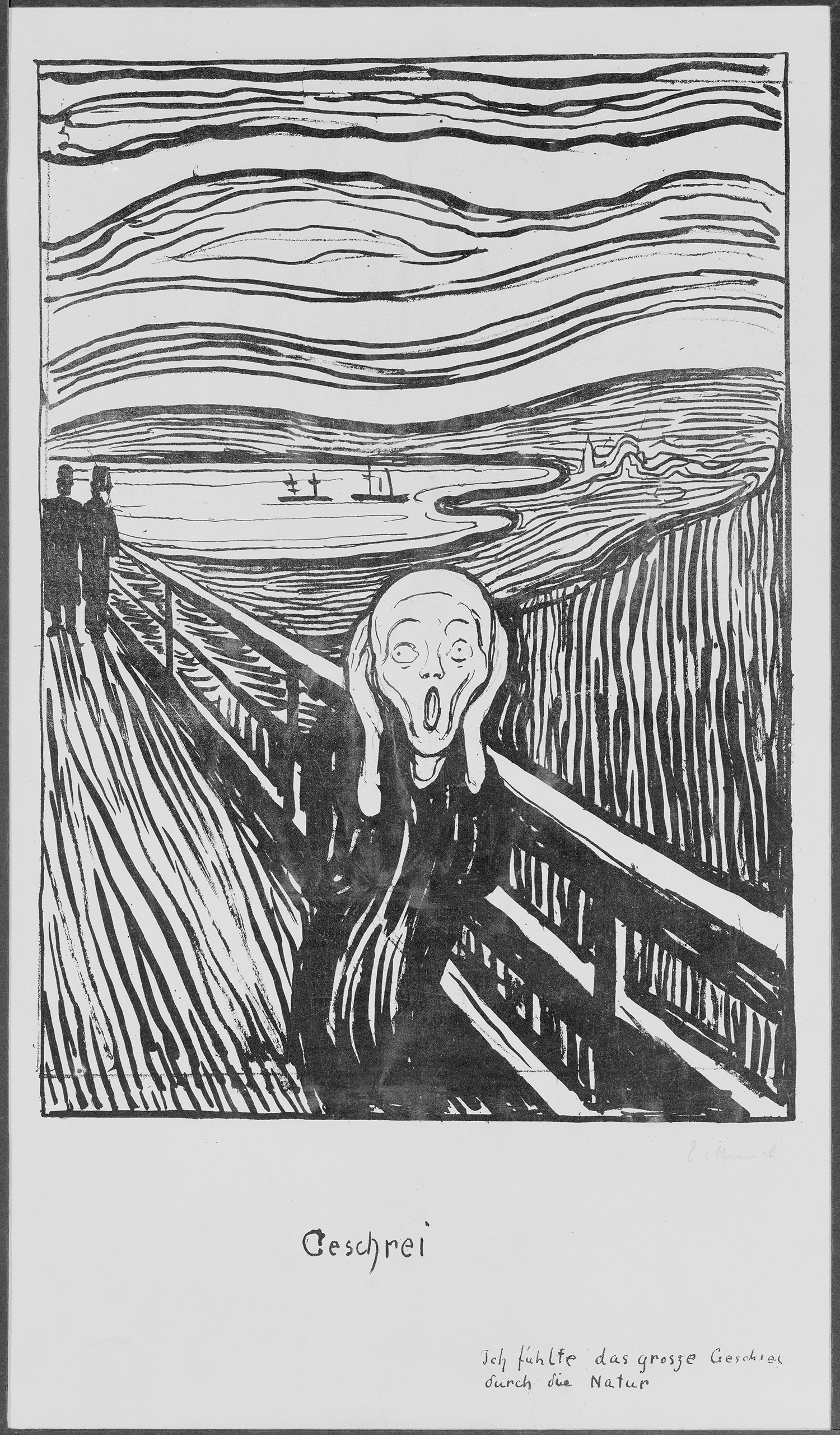

(Image)

Thursday, September 27, 2012

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

Public Jesus (Chapter One)

Last week I mentioned that every year our church does something called The Blitz. This year were using Public Jesus by Tim Suttle. In hopes of priming the pump for this conversation, I thought I might post a few thoughts and questions from the book.

Chapter one of Public Jesus is called, "To be a Human Being in the World." Here we encounter several things:

(1) Being born and becoming conscious of a world that was here before we were.

(2) The Christian version, or story, about how we got here and why, specifically related to the book of Genesis and person of Jesus as it relates to the creation and redemption of the world.

(3) Being salt and light, which is about the public nature of Christianity.

At one point near the end of chapter Tim says, "The church is the way God is now physically present to the world."

I'm curious how this sounds to North American Protestant Evangelicals (or NAPEs as I like to call them, of which I am one) who are typically prone to view God as utterly accessible: We have a personal relationship with Jesus, God hears every single one of our prays AND answers them, and speaks to us in the process with an uncanny kind of clarity. NAPEs lean into the utterly accessible (and often times instant) side of God's relationship with the world.

It tends to be that NAPEs overplay the instant and accessible card to the detriment of a more robust ecclesiology that speaks of God being present to the world through the church. I think there's a good conversation waiting to be had here about what it means to say, to put it another way (a la Steve McCormick and the Orthodox tradition), that the church is God's new epiphany in the world, i.e. that the church is the new way through whom God is primarily related to the world. For most NAPEs we want to recapture a more robust ecclesiology BUT, I think, not without losing the sense that God has not limited the way He is present to the world. In other words, can we not also say that God does in fact move redemptively outside of the church as well?

What do you think?

Chapter one of Public Jesus is called, "To be a Human Being in the World." Here we encounter several things:

(1) Being born and becoming conscious of a world that was here before we were.

(2) The Christian version, or story, about how we got here and why, specifically related to the book of Genesis and person of Jesus as it relates to the creation and redemption of the world.

(3) Being salt and light, which is about the public nature of Christianity.

At one point near the end of chapter Tim says, "The church is the way God is now physically present to the world."

I'm curious how this sounds to North American Protestant Evangelicals (or NAPEs as I like to call them, of which I am one) who are typically prone to view God as utterly accessible: We have a personal relationship with Jesus, God hears every single one of our prays AND answers them, and speaks to us in the process with an uncanny kind of clarity. NAPEs lean into the utterly accessible (and often times instant) side of God's relationship with the world.

It tends to be that NAPEs overplay the instant and accessible card to the detriment of a more robust ecclesiology that speaks of God being present to the world through the church. I think there's a good conversation waiting to be had here about what it means to say, to put it another way (a la Steve McCormick and the Orthodox tradition), that the church is God's new epiphany in the world, i.e. that the church is the new way through whom God is primarily related to the world. For most NAPEs we want to recapture a more robust ecclesiology BUT, I think, not without losing the sense that God has not limited the way He is present to the world. In other words, can we not also say that God does in fact move redemptively outside of the church as well?

What do you think?

Tuesday, September 25, 2012

Top ten Mitt Romney solutions to our problems

On Facebook this morning, I took a jab at Obama saying: "What

do you think will be talked about more today: (1) The controversial

Seahawk touchdown or (2) that as the foreign heads of state were

gathering for the United Nations convention, the Obama's went on The

View?" See Dana Milbank's article here.

(I really should of jabbed the NFL refs as well. Oh well, next time.)

For the sake of being fair, here's a jab for Mitt as well (and no I'm not crossing sports references). Check out Juan Cole's top ten Mitt Romney solutions to our problems.

Monday, September 24, 2012

In the interest of have a better political conversation... It's all political

This is part one in a serious of posts I'm calling: In the interest of having a better political conversation...

So, in the interest of having a better political conversation... It's all political.

Politicians will typically pivot to blame their opposition for saying or doing things merely for the sake of playing politics. Case in point: Mitt Romney's criticism of Barak Obama's response to embassy attack in Libya, to which Ben LaBolt (Obama's campaign spokesman) responded that he was "shocked" that during a time like this Romney "would choose to launch a political attack."

While it's not shocking to me that people blame other people for merely playing politics when there are real issues at stake (because it happens all the time), it's frustrating that this kind of slam goes on often times without regard to the fact that it is all political and it can't be any other way and that this is not a bad thing or something to be feared. Politics, as such, isn't the enemy and shouldn't be used as a means by which one politician asserts him or herself as better than another. In fact, when you hear a politician blaming another politician for merely playing politics, you should assume that the politician doing the blaming is trying to get their agenda over on you with you know it. That's deceiving.

Politicians all over the place stand up and tell you why their plan is better than the other persons, but it's so duplicitous because as soon as they see an opportunity to take political advantage, mostly in regards to winning an election, they blame the other person for playing politics, thus setting themselves up as being more like the average person, who apparently is not political. This is demeaning.

Inherent in the slam that someone is playing politics is this notion that that person has some kind of (secret) agenda that's working you over, which is why you shouldn't trust professional politicians who spend their lives playing politics just so they can stay in power. However, inherent in the slam itself, that someone is merely playing politics, is also the notion that the one doing the slamming has a (secret) agenda, as well, that's working you over. This is what the person doing that blaming doesn't want you to know because then they can't try to back door you with their agenda.

Why not be forthcoming with it in the first place? It's all politics, which is not a contested idea. It's regularly assumed by political scientists and theologians, dating all the way back to Aristotle. Real political people don't try to hide that fact that they might have some good ideas about how this world should be organized. Whether you agree with them or not is a whole other issue, but at least they are forthcoming. And that would be refreshing.

So, watch out for what I'm calling the playing-politics-blame-game because really it's all political.

So, in the interest of having a better political conversation... It's all political.

Politicians will typically pivot to blame their opposition for saying or doing things merely for the sake of playing politics. Case in point: Mitt Romney's criticism of Barak Obama's response to embassy attack in Libya, to which Ben LaBolt (Obama's campaign spokesman) responded that he was "shocked" that during a time like this Romney "would choose to launch a political attack."

While it's not shocking to me that people blame other people for merely playing politics when there are real issues at stake (because it happens all the time), it's frustrating that this kind of slam goes on often times without regard to the fact that it is all political and it can't be any other way and that this is not a bad thing or something to be feared. Politics, as such, isn't the enemy and shouldn't be used as a means by which one politician asserts him or herself as better than another. In fact, when you hear a politician blaming another politician for merely playing politics, you should assume that the politician doing the blaming is trying to get their agenda over on you with you know it. That's deceiving.

Politicians all over the place stand up and tell you why their plan is better than the other persons, but it's so duplicitous because as soon as they see an opportunity to take political advantage, mostly in regards to winning an election, they blame the other person for playing politics, thus setting themselves up as being more like the average person, who apparently is not political. This is demeaning.

Inherent in the slam that someone is playing politics is this notion that that person has some kind of (secret) agenda that's working you over, which is why you shouldn't trust professional politicians who spend their lives playing politics just so they can stay in power. However, inherent in the slam itself, that someone is merely playing politics, is also the notion that the one doing the slamming has a (secret) agenda, as well, that's working you over. This is what the person doing that blaming doesn't want you to know because then they can't try to back door you with their agenda.

Why not be forthcoming with it in the first place? It's all politics, which is not a contested idea. It's regularly assumed by political scientists and theologians, dating all the way back to Aristotle. Real political people don't try to hide that fact that they might have some good ideas about how this world should be organized. Whether you agree with them or not is a whole other issue, but at least they are forthcoming. And that would be refreshing.

So, watch out for what I'm calling the playing-politics-blame-game because really it's all political.

Saturday, September 22, 2012

Monk Habits for Everyday People

“The desperate need today is not for

a greater number of intelligent people of gifted people, but deep people”

(Richard Foster). This is how Dennis Okholm opens his book, Monk Habits for Everyday People. Plain

and simple: the sheer noise, distraction, stimulation, and escapism that is

American culture is as much against the way of Jesus as a BoSox fan is against

the Yankees. While American Christians might claim the desire to cultivate such

a deep spirituality, the actual practice of cultivating that spirituality often

times barely gets off the ground, if it flies at all. People spend their lives either

reading about it, without doing anything about it. Or they spend their energy just

doing a whole bunch of things without any sense of meaning or understanding

that leads to wisdom. Or they stand off to side, ignoring the nudge towards

that deeper spirituality they feel in their hearts, hoping that it will just go

away so that they can get back to whatever cushy life they’ve created for

themselves.

“The desperate need today is not for

a greater number of intelligent people of gifted people, but deep people”

(Richard Foster). This is how Dennis Okholm opens his book, Monk Habits for Everyday People. Plain

and simple: the sheer noise, distraction, stimulation, and escapism that is

American culture is as much against the way of Jesus as a BoSox fan is against

the Yankees. While American Christians might claim the desire to cultivate such

a deep spirituality, the actual practice of cultivating that spirituality often

times barely gets off the ground, if it flies at all. People spend their lives either

reading about it, without doing anything about it. Or they spend their energy just

doing a whole bunch of things without any sense of meaning or understanding

that leads to wisdom. Or they stand off to side, ignoring the nudge towards

that deeper spirituality they feel in their hearts, hoping that it will just go

away so that they can get back to whatever cushy life they’ve created for

themselves.

Why Benedictine Spirituality? For

one, because it’s so absolutely contra-celebrity. American Christians

(specifically Evangelicals) tend towards the celebrity. We switch churches for

the one with the new, rising star. Pastors write books, leave their churches,

and go on book tours. Fame is the measure of truthfulness, aparantly. We flock

to the bookstores to buy the latest book that we think will cure our spiritual

apathy and delusion, rather than turning to ancient words of the Scripture, and

the Psalms in particular, in order to get our bearings.

Benedictine spirituality is largely

a rule of life comprised of the Scripture. It was written by a man who had so

digested those ancient holy words that they couldn’t help but invade what he

was writing to his monastic community. Scripture is the original rule, but

Scripture is always accompanied by the lived experience of the people, which

meant that it spoke to them personally. Also, in its day, the Benedictine Rule

was not the hot new answer to all of our questions. Benedict stands in history

as one of the great consolidators of monastic spirituality. He gathered the

essentials and put them all in one place, leaving off to the side some of more

arcane and, to be honest, just downright weird aspects of the monastic life

(just read some of the sayings of the desert fathers). The Rule was utterly

traditional, contrary to most writers today who want to sell us the latest new

thing, some answer that they have discovered that no one else thought us. As a

rule, the further back, and thus more inclusive one goes in the tradition, the

better. New insights will be gained that will help us more forward, but not

without a deep reading of the past. This is how you know who you can trust.

Okholm notes several reasons why

Protestants might benefit from a Benedictine spirituality:

1. To their credit, Protestants are

historically bent towards piety to begin with: daily devotions, regular

worship. This is a good thing. Where a Benedictine Spirituality becomes

immediately helpful is in regards to the Protestant (especially Evangelical)

bent towards individualism. The monastic community (the cloister) recognizes the

beautiful relationship between action and contemplation, community and

solitude, engagement and withdrawal.

2. It forces Protestants to embrace

a wider ecclesiology. Again, tending towards individualism, Protestants

(especially Evangelicals) seem to write off too easily other parts of the Christian

tradition. One way to know if you’re in the company of a safe and healthy

pastor/speaker/theologian is to see how widely they read. Do they read only the

books produced by Evangelical celebrities, kitsch pop-culture Christian fluff,

or do they readi Roman Catholics, Orthodox, Anabaptist, Anglican, African,

Latino folks as well. (Note: this doesn’t mean that they are experts in all of

this, but that in some way, shape, and form, their imaginations are being

influences in the widest possible way. Narrow influences are an indication of

narrow imagination.)

3. Protestants are good at doctrine

but bad at living. The rule is a way of putting the words of Scripture and theology

reflection into practice. It really is about living good days.

4. The Protestant emphasis on

Scripture blends nicely with the Benedictine Rule. As I said before, Scripture

is the original rule, but Scripture is always accompanied by the lived

experience of the people. The Rule arose out of the depths of a man who had so

immersed himself in the Scripture that it couldn’t help but invade what he was

writing to his community.

5. If nothing else, Protestants tend

to write off Benedictine Spirituality without really understanding it. We need

at least become better acquainted with it because it’s a part of our past.

6. Protestants are typically instant

kind of Christians: Instant access to God, instant answer to prayer. We don’t

do well with waiting. Benedictine Spirituality sees Christian maturity as

something one attains only through a disciplined way of life. It’s the image of

the athlete in training. The monastics called it asceticism. While Protestants

often look back on the moment of their conversion experience and wonder why

things are not as good as it was back then, the monk sees life as a kind of training

for the kingdom way of life. We grow and mature, like a tree, into the fullness

of life with God in Christ.

Thoughts?

Next time: Benedicts thoughts on

learning how to be silent.

Friday, September 21, 2012

"I just want to get closer to God" - On Mission, Worship, and Knowing God

Perhaps the most difficult thing for Protestant Evangelicals (PE) to embrace is that knowledge of God is absolutely related to mission. To put it bluntly, we cannot know God unless we are on mission with God. The PE vernacular of having a personal relationship with Jesus is often practiced only in the form of an emotional high during the worship service. No emotion, no high, no knowledge of God, thus the PE state of disillusionment where one is always trying to get closer to God. It's utterly circular and ultimately defeating, I know from first hand experience.

If I may borrow the PE vernacular, if you want to get closer to God (to know God), then participate in God's mission. One of the most concise places to begin to understand what God's mission is in the world is found in Matthew 25, which talks about feeding the hungry, quenching the thirst of thirsty, practicing hospitality (especially to strangers), clothing the naked, tending the sick, and visiting the prisoner. A better, more comprehensive place to begin would be the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7). This is just for starters...

If I may step back a bit from my original blunt statement that we can't know God unless we are on mission with God: I do believe that God speaks to those of us who are not on mission with Him, thus some kind of knowledge of God can be had. It's possible to know God is speaking to you and not to listen. In some sense you know God even if you refuse Him. My critique is for those PE's who claim to have a personal relationship with Jesus Christ who measure the status of that relationship according to an emotional high.

In some ways this is a tried argument, but until it seems there's an obvious shift in the other direction then it's important to talk about. In my region of the world, a certain kind of PE is still highly operative, whereby people still barely connect what happens during the worship service with what happens during the week. Many still can't imagine how the movements of worship (the liturgy) have a certain kind of shape to them (or at least they should, which could beg the question of what's actually happening in the worship service at your church). James K. A. Smith recently address a part of this question in a article, except that he was talking the other side of the issue which said that we don't need to gather for worship because we worship simply by living in the world. In any case, the claim for the importance of the liturgy of worship must be made.

Worship is a "hot spot," as Smith says, where we are brought in close proximity to God/the ways of God/the story of God, etc. In such close proximity, we are drawn in, transformed, and sent back out into the world. That's the shape of worship. To put it another way, God breathes us into Himself (gathers us) and then breathes us back out (scatters us). When we are breathed in, we catch a vision of the kingdom through the movements of worship. We practice the kingdom in worship and then when we are breathed back out into the world, we live the kingdom life. It's not one way or the other. They work together. Yes, one knows God through the Eucharist but only because the Eucharist is not limited to merely the bread and cup in worship. Each meal we share with each other is a kind of Eucharist.

It may just be that if we want to know God, we should at least begin to share meals together (a good "strategy" for community groups, by the way, rather than simply doing studies together, although you'd be surprised how quickly the conversation around a table can become about God). It may just be that to know God, you share you clothes, your food, your water, your time, your energy, your resources, your skills, your law practice, your words, your thoughts, your home, your laws, your school...

We don't know what God's mission is unless He draws us into it and shows us the way (worship) and by showing us the way He shows us Himself.

What do you think?

If I may borrow the PE vernacular, if you want to get closer to God (to know God), then participate in God's mission. One of the most concise places to begin to understand what God's mission is in the world is found in Matthew 25, which talks about feeding the hungry, quenching the thirst of thirsty, practicing hospitality (especially to strangers), clothing the naked, tending the sick, and visiting the prisoner. A better, more comprehensive place to begin would be the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7). This is just for starters...

If I may step back a bit from my original blunt statement that we can't know God unless we are on mission with God: I do believe that God speaks to those of us who are not on mission with Him, thus some kind of knowledge of God can be had. It's possible to know God is speaking to you and not to listen. In some sense you know God even if you refuse Him. My critique is for those PE's who claim to have a personal relationship with Jesus Christ who measure the status of that relationship according to an emotional high.

In some ways this is a tried argument, but until it seems there's an obvious shift in the other direction then it's important to talk about. In my region of the world, a certain kind of PE is still highly operative, whereby people still barely connect what happens during the worship service with what happens during the week. Many still can't imagine how the movements of worship (the liturgy) have a certain kind of shape to them (or at least they should, which could beg the question of what's actually happening in the worship service at your church). James K. A. Smith recently address a part of this question in a article, except that he was talking the other side of the issue which said that we don't need to gather for worship because we worship simply by living in the world. In any case, the claim for the importance of the liturgy of worship must be made.

Worship is a "hot spot," as Smith says, where we are brought in close proximity to God/the ways of God/the story of God, etc. In such close proximity, we are drawn in, transformed, and sent back out into the world. That's the shape of worship. To put it another way, God breathes us into Himself (gathers us) and then breathes us back out (scatters us). When we are breathed in, we catch a vision of the kingdom through the movements of worship. We practice the kingdom in worship and then when we are breathed back out into the world, we live the kingdom life. It's not one way or the other. They work together. Yes, one knows God through the Eucharist but only because the Eucharist is not limited to merely the bread and cup in worship. Each meal we share with each other is a kind of Eucharist.

It may just be that if we want to know God, we should at least begin to share meals together (a good "strategy" for community groups, by the way, rather than simply doing studies together, although you'd be surprised how quickly the conversation around a table can become about God). It may just be that to know God, you share you clothes, your food, your water, your time, your energy, your resources, your skills, your law practice, your words, your thoughts, your home, your laws, your school...

We don't know what God's mission is unless He draws us into it and shows us the way (worship) and by showing us the way He shows us Himself.

What do you think?

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

Public Jesus

Every year our church does something

called The Blitz. The idea is that if you want to tackle the quarter back, you

call for a blitz. Substitute quarterback

with community and you get The Blitz.

Every year we try to tackle community. Pretty simple (it’s a metaphor). Each year we intentionally sync

up around some kind of teaching/practice. That's the gist.

This year we're using Public Jesus by TimSuttle. (By the way, if you haven’t already checked out some of the stuff that

The House Studio is putting out, you should. It’s great for small groups and it

features people such as Stanley Hauerwas and Walter Brueggemann, people who

have been extremely influential in my own development.)

Tim is a good friend and pastor of

Redemption Church here in Olathe, KS. I’m excited to dig into this book with

the rest of the Redemption Church people. And maybe others, if you all want to participate. I’m sure it will provoke many

thoughts and questions that will challenge our assumptions about what it means

to confess that Jesus is Lord.

In the introduction we get a little

taste of what to expect:

- “What role should our faith play in

public life?”

- What does it mean to say “the public

square belongs to God”?

- “What would the world be like if God

were in charge?”

- How does a theology of creation inform

this?

- Why is Jesus good news?

- What is the mission of God?

- Why are secularism and

fundamentalism the most common ditches people fall in to?

Perhaps it could be said that the

heart of Public Jesus is a

“[wrestling] with all kinds of questions about what it would mean for us to

live our lives as though we believe Jesus is Lord of all” (16).

Over the next few weeks, I hope to

prime the pump a bit by noting some of what’s in store for us

here.

Here's a quote:

Also, check out one of the videos here."Living in the way of Jesus cannot be merely a personal, private thing because faith is meant to impact every aspect of life. God cares about all of life. I cannot check my faith at the door when I go into the supermarket, drive my car, pay my taxes, give to a charity, volunteer, cash my paycheck, or vote. Everything I do in my life - be it private or public - is meant to be informed by my most basic identity: I am a follower of Jesus Christ, a Christian. When I live in faithfulness to Jesus as I navigate public space, I believe that I am participating in the deep and seminal reality that God is trying to bring right order to the world. My faith in Jesus must impact all that I say and do when I inhabit public space."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)