At a certain point during our weekly worship gathering, I get to stand up and lead our church in a modified version of the prayers of the people. We always begin this movement of worship with silence and then confession. The silence lasts somewhere around fifteen seconds, although I always shoot for thirty. As little and insignificant as that may seem, it's intentional; and because it's a part of the liturgy of worship it's deep with meaning.

Chapter three of Dennis Okholm's book, Monk Habits for Everyday People, is called "Learning to Listen." (Read my first post here.)

Silence is not just about not talking. In fact, Benedict never urged for total silence. The restraint of speech was a matter of hospitality. Because they all lived together in a monastic community, silence was encouraged over an excessive amount of talking. Thus, one should speak only when words were necessary. Of course, this begs the question as to how one knows when words are and are not necessary. This is partly why this community practiced intentional times of silence. If you never stop talking then you are not able to know when is the right time to be silent. By practicing silence we learn when to speak and when not to speak. Of course, when they spoke intentionally it was in the form prayer, specifically reading the Psalms. This says a lot about how we learn to speak as Christians. When you begin to follow Jesus, you are just not able to speak maturely about Him. You have to learn how to speak and the Psalms, for example, can train us in this. Consider that Paul spent fourteen years after his conversion learning before he spoke in any sort of public and authoritative way. This should make us pause.

Okholm quotes Michael Casey on this, a point speaks to North American cultures situation of just utter noise. "Talk restricts our capactiy to listen, it banishes mindfulness and opens the door to distraction and escapism. Talking too much often convinces us of the correctness of our own conclusions and leads some into thinking they are wise. IT can be a subtle exercise in arrogance and superiority. Often patters of dependence, manipulation, and dominance are established and maintained by the medium of speech."

In case you're ever wondering, this is why we take time to be silent in worship. Too much is riding on the church's capacity to know when to speak and when to be silent, as well as how to speak and how to be silent.

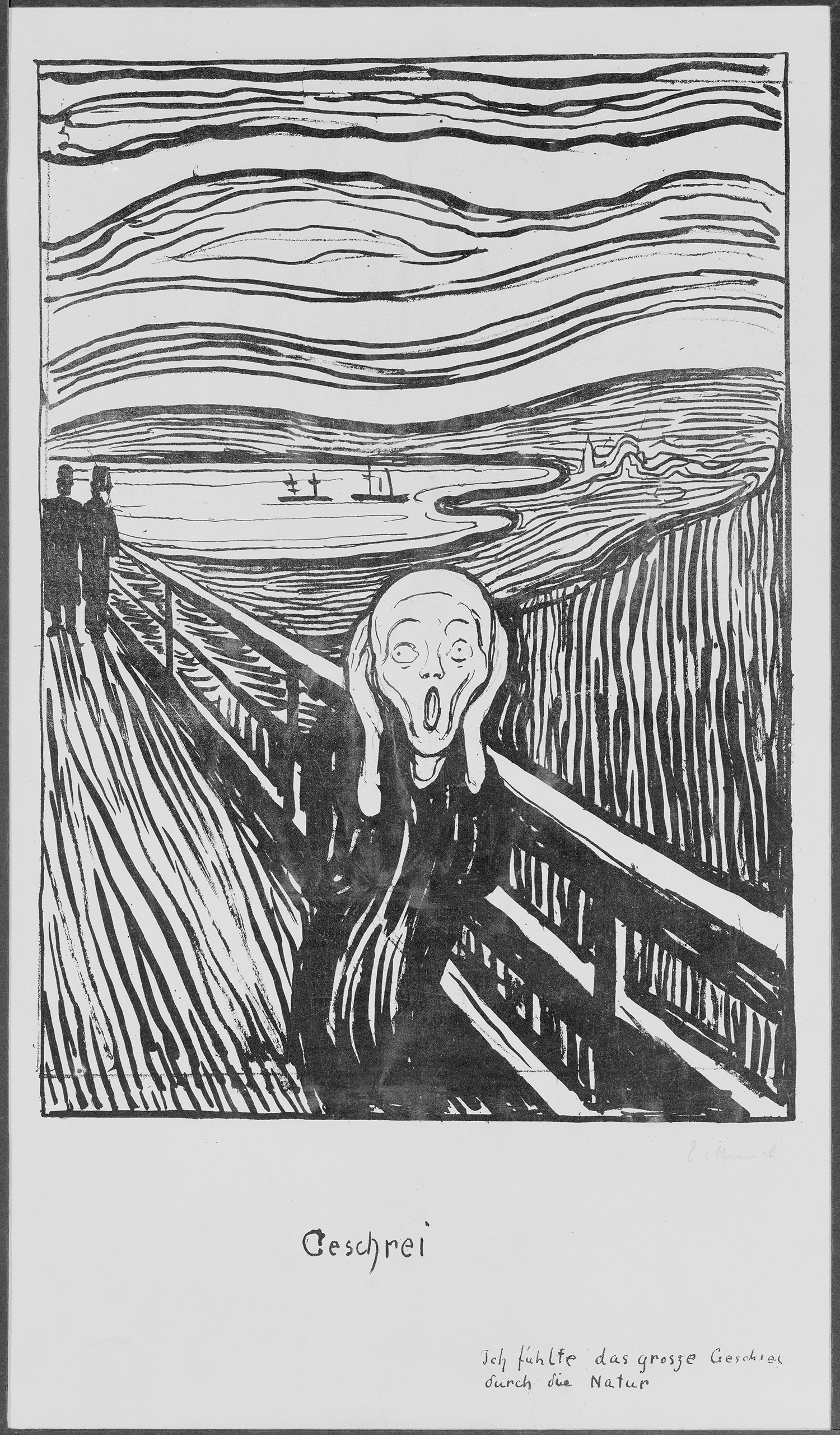

(Image)

Showing posts with label Dennis Okholm. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Dennis Okholm. Show all posts

Thursday, September 27, 2012

Saturday, September 22, 2012

Monk Habits for Everyday People

“The desperate need today is not for

a greater number of intelligent people of gifted people, but deep people”

(Richard Foster). This is how Dennis Okholm opens his book, Monk Habits for Everyday People. Plain

and simple: the sheer noise, distraction, stimulation, and escapism that is

American culture is as much against the way of Jesus as a BoSox fan is against

the Yankees. While American Christians might claim the desire to cultivate such

a deep spirituality, the actual practice of cultivating that spirituality often

times barely gets off the ground, if it flies at all. People spend their lives either

reading about it, without doing anything about it. Or they spend their energy just

doing a whole bunch of things without any sense of meaning or understanding

that leads to wisdom. Or they stand off to side, ignoring the nudge towards

that deeper spirituality they feel in their hearts, hoping that it will just go

away so that they can get back to whatever cushy life they’ve created for

themselves.

“The desperate need today is not for

a greater number of intelligent people of gifted people, but deep people”

(Richard Foster). This is how Dennis Okholm opens his book, Monk Habits for Everyday People. Plain

and simple: the sheer noise, distraction, stimulation, and escapism that is

American culture is as much against the way of Jesus as a BoSox fan is against

the Yankees. While American Christians might claim the desire to cultivate such

a deep spirituality, the actual practice of cultivating that spirituality often

times barely gets off the ground, if it flies at all. People spend their lives either

reading about it, without doing anything about it. Or they spend their energy just

doing a whole bunch of things without any sense of meaning or understanding

that leads to wisdom. Or they stand off to side, ignoring the nudge towards

that deeper spirituality they feel in their hearts, hoping that it will just go

away so that they can get back to whatever cushy life they’ve created for

themselves.

Why Benedictine Spirituality? For

one, because it’s so absolutely contra-celebrity. American Christians

(specifically Evangelicals) tend towards the celebrity. We switch churches for

the one with the new, rising star. Pastors write books, leave their churches,

and go on book tours. Fame is the measure of truthfulness, aparantly. We flock

to the bookstores to buy the latest book that we think will cure our spiritual

apathy and delusion, rather than turning to ancient words of the Scripture, and

the Psalms in particular, in order to get our bearings.

Benedictine spirituality is largely

a rule of life comprised of the Scripture. It was written by a man who had so

digested those ancient holy words that they couldn’t help but invade what he

was writing to his monastic community. Scripture is the original rule, but

Scripture is always accompanied by the lived experience of the people, which

meant that it spoke to them personally. Also, in its day, the Benedictine Rule

was not the hot new answer to all of our questions. Benedict stands in history

as one of the great consolidators of monastic spirituality. He gathered the

essentials and put them all in one place, leaving off to the side some of more

arcane and, to be honest, just downright weird aspects of the monastic life

(just read some of the sayings of the desert fathers). The Rule was utterly

traditional, contrary to most writers today who want to sell us the latest new

thing, some answer that they have discovered that no one else thought us. As a

rule, the further back, and thus more inclusive one goes in the tradition, the

better. New insights will be gained that will help us more forward, but not

without a deep reading of the past. This is how you know who you can trust.

Okholm notes several reasons why

Protestants might benefit from a Benedictine spirituality:

1. To their credit, Protestants are

historically bent towards piety to begin with: daily devotions, regular

worship. This is a good thing. Where a Benedictine Spirituality becomes

immediately helpful is in regards to the Protestant (especially Evangelical)

bent towards individualism. The monastic community (the cloister) recognizes the

beautiful relationship between action and contemplation, community and

solitude, engagement and withdrawal.

2. It forces Protestants to embrace

a wider ecclesiology. Again, tending towards individualism, Protestants

(especially Evangelicals) seem to write off too easily other parts of the Christian

tradition. One way to know if you’re in the company of a safe and healthy

pastor/speaker/theologian is to see how widely they read. Do they read only the

books produced by Evangelical celebrities, kitsch pop-culture Christian fluff,

or do they readi Roman Catholics, Orthodox, Anabaptist, Anglican, African,

Latino folks as well. (Note: this doesn’t mean that they are experts in all of

this, but that in some way, shape, and form, their imaginations are being

influences in the widest possible way. Narrow influences are an indication of

narrow imagination.)

3. Protestants are good at doctrine

but bad at living. The rule is a way of putting the words of Scripture and theology

reflection into practice. It really is about living good days.

4. The Protestant emphasis on

Scripture blends nicely with the Benedictine Rule. As I said before, Scripture

is the original rule, but Scripture is always accompanied by the lived

experience of the people. The Rule arose out of the depths of a man who had so

immersed himself in the Scripture that it couldn’t help but invade what he was

writing to his community.

5. If nothing else, Protestants tend

to write off Benedictine Spirituality without really understanding it. We need

at least become better acquainted with it because it’s a part of our past.

6. Protestants are typically instant

kind of Christians: Instant access to God, instant answer to prayer. We don’t

do well with waiting. Benedictine Spirituality sees Christian maturity as

something one attains only through a disciplined way of life. It’s the image of

the athlete in training. The monastics called it asceticism. While Protestants

often look back on the moment of their conversion experience and wonder why

things are not as good as it was back then, the monk sees life as a kind of training

for the kingdom way of life. We grow and mature, like a tree, into the fullness

of life with God in Christ.

Thoughts?

Next time: Benedicts thoughts on

learning how to be silent.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)